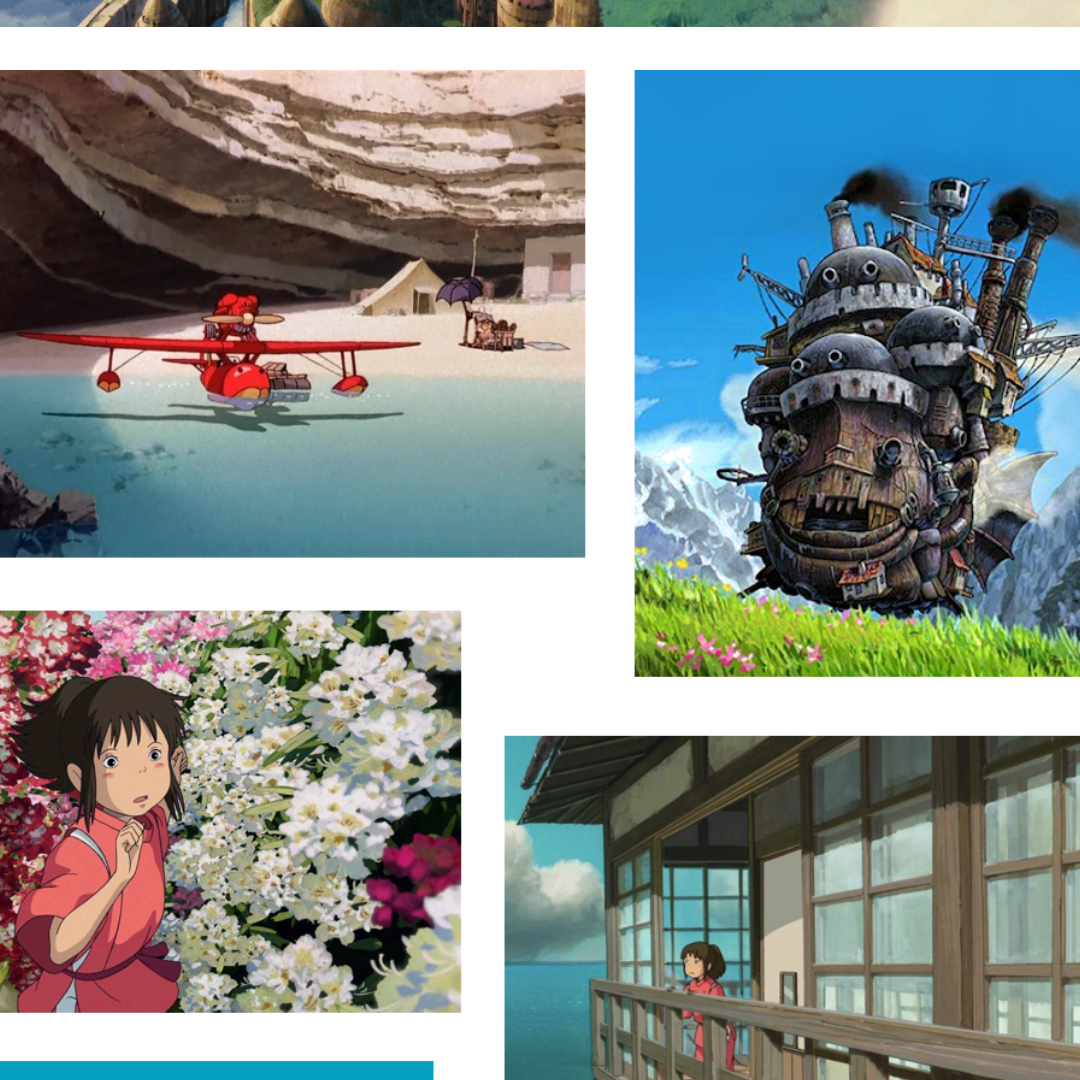

If you are a fan of animated movies, you most likely have heard of have of My Neighbor Totoro, Howl’s Moving Castle or Spirited Away.

All of these films were produced by Japanese director Hayao Miyazaki under the Japanese animation film company, Studio Ghibli. While Miyazaki might be the popular face of Studio Ghibli, he surely isn’t the only mastermind that has molded Japan’s most illustrious animation company. Studio Ghibli’s success should also be credited to the company’s producer, Toshio Suzuki and their other storytelling phenom, the late Isao Takahata, director of The Grave of the Fireflies and The Tale of Princess Kaguya.

These three creatives and long time collaborators are pictured below in Studio Ghibli’s 2013 documentary, The Kingdom of Dreams and Madness.

In 1985, Miyazaki, Suzuki and Takahata co-founded Studio Ghibli. They took this leap of faith after the success of their 1984 film, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, a movie that saw them win the highly acclaimed Kinema Junpo Reader’s Choice Award for Best Film the following year. Based on the manga series written and drawn by Miyazaki, Nausicaä had Takahata as its producer and Miyazaki as its director. Six years later, Miyazaki and Takahata would work together once more in Studio Ghibli’s 1991 film Only Yesterday. This time, Miyazaki would produce, and Takahata would take the mantle as director.

In a documentary called the Making of ‘Only Yesterday’, Miyazaki confessed that only Takahata had the skill set to complete the movie.

“I couldn’t do it. I don’t have such skills. And the only person to have such skills was Takahata.”

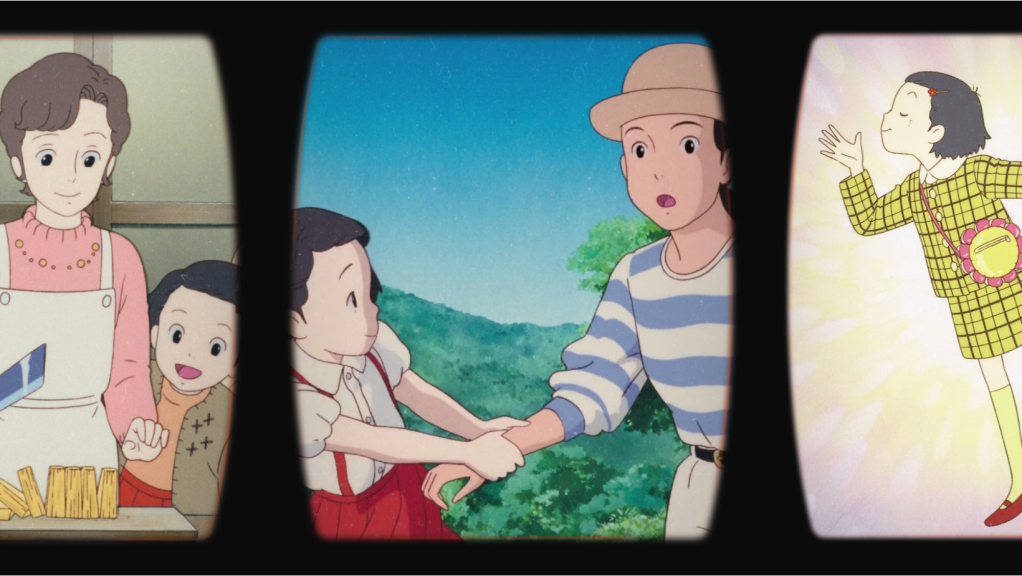

Only Yesterday is based on a 1982 manga called Omohide Poro Poro translated to ‘Memories come Tumbling Down’ in English by Okamoto Hotaru and illustrated by Tone Yuko. Initially, both Takahata and Miyazaki struggled to envision how they could turn the beloved child manga into a movie. That was until Takahata got the brilliant idea of maturing the 11-year-old protagonist into a 27-year-old adult who reminiscences about her younger self. 15 grueling months later, Takahata completed his masterpiece. Studio Ghibli released Only Yesterday in 1991. It became the highest-grossing film in Japan that year.

Only Yesterday follows Taeko Okajima, a 27-year-old unmarried woman who lives in Tokyo in 1982. Needing an escape from this metropolitan world, she decides to go on a week-long vacation to visit distant family members in Yamagata Prefecture.

Yamagata sits only 5 to 7 hours away from Tokyo in the North of Japan, but it feels like it is a world away. Where Tokyo is covered in concrete, Yamagata is dotted by tall cedar trees, mountains and… safflowers. This bright orange flower and its hundreds-year-long cultivation in Japan’s Yamagata prefecture serves as the backdrop of the movie. When Taeko goes to Yamagata in the summer, it is for this reason: to help family friends whose lives are dedicated to picking, processing and extracting the red dye from these brightly pigmented plants.

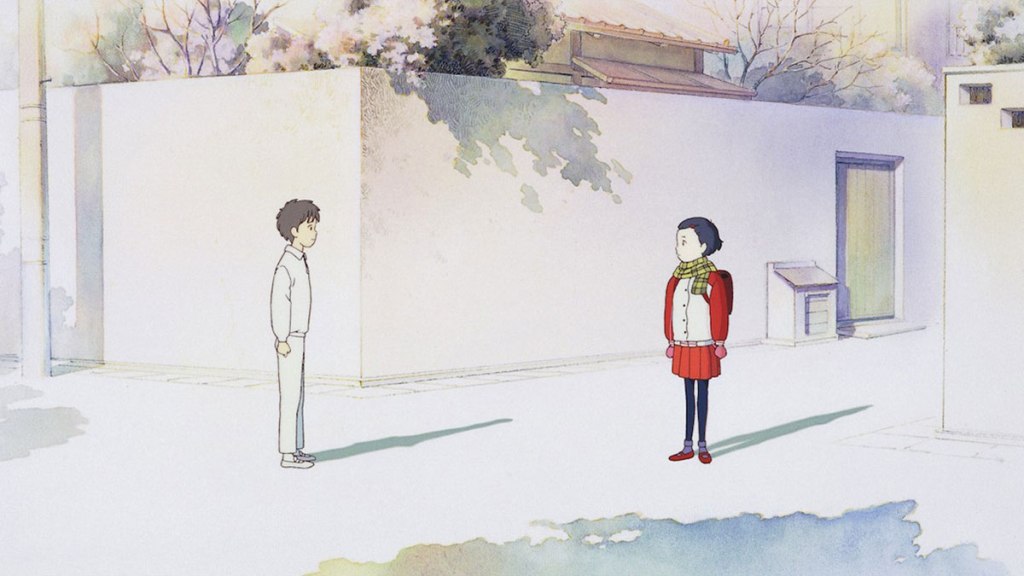

Although she expected her trip from Tokyo to Yamagate to be a solitary journey, she quickly finds herself accompanied by an unexpected visitor: her fifth-grade self from 1966.

This bubbly and quirky child forces Taeko to reflect on her past: her school boy crush, the first time she tasted the sweetness of a pineapple (an imported luxury in Japan at the time) and summer days spent languishing in steamy hot springs. At face value, these moments may seem simple, even insubstantial. But, Takahata does a brilliant job at demonstrating how even mundane events have a long lasting impact on Taeko’s memory. Such superb writing makes the viewer also reflect on one’s childhood– “What memories from childhood have followed me into adulthood?”

For Taeko, it is a person, her former school mate Shuji Hirota, or rather it is the feeling she experiences when she realizes he has a crush on her: both the awkwardness and the thrill.

“Do you like sun or clouds?… A sunny day or a cloudy day? Which do you like best,” Hirota asks her, his voice timid but determined.

“Cloudy,” a young Taeko shyly responds.

A smile spreads on Hirota’s face, “Oh, we’re alike!”

The interaction may have been short, but the impact is both immediate and long-lasting. The following scene shows a younger Taeko soaring into a romantic pastel pink and blue sky. Although the sweet exchange happened fifteen years prior, an older Taeko can’t help but blush and giggle at the innocent and exciting moment.

“Rainy days…cloudy days, or sunny days…which do you like? Oh…we’re alike,” she whispers to herself.

But endearing moments aren’t the only ones that stick with her.

There was the time she failed a math test and her older sister picked on her. Or the time that her father was so angry after she had a fit about not wanting a hand-me-down that he slapped her in the face. There was the time when Taeko gets an outstanding remark on her essay, and all her mother has to say about it is, “I think it would be a whole lot better if you were a girl who ate what she’s given instead of a girl whose essays are just a little bit better than everyone else’s.”

Over the years, these vulnerable moments pile onto one another. Taeko struggles with the fact that she can not let go of these memories as easily as the people around her seemingly have.

“Are you still dwelling on that? Taeko, you still hang on to things don’t you?” her older sister asks her in the beginning of the movie.

“I guess I never was able to put that behind me,” she responds with a sad smile.

The words are striking and melancholic. But Taeko’s burden is not entirely her own. In many ways, her uneasiness is a combination of what she has been told throughout her childhood and her young adult life. As the youngest in her family, she has always felt somewhat unmoored. She wears her sister’s hand-me-downs. She seems to only annoy her mother. She yearns to be recognized as special.

Like so much from childhood, these desires and regrets follow Taeko into adulthood. Even so, it turns out our protagonist is not alone in this struggle to decipher ‘yesterday’ from ‘today’ and ‘tomorrow.’ Japan also faced a similar identity crisis.

In the 1980s, Japan experienced a “crisis of nostalgia.” From the 1960s into the 1980s, its cities experienced unprecedented economic growth. The time between 1955 and the early 1960s marked the end of the country’s postwar reconstruction, and a push toward modernization. As such, Japan began focusing its attention on developing its urban life. Cities like Tokyo, Osaka and Nagoya were selected to become the country’s industrial hubs. In December 29, 1989, the Tokyo stock market reached an all time high. With this economic success, however, came with fears that the country was losing itself in the opulence of consumerism.

Cities became congested and polluted. Japan went through two oil crises. People began fearing that westernization was eroding Japan’s culture. And so with this economic boom, came “the retro boom”, a period that romanticized Japanese rural life and the country’s pre-war and pre-Depression past. Japanese social critic Akatsuka Yoshio named this period in the 1980s as a “Retrospective Age.”

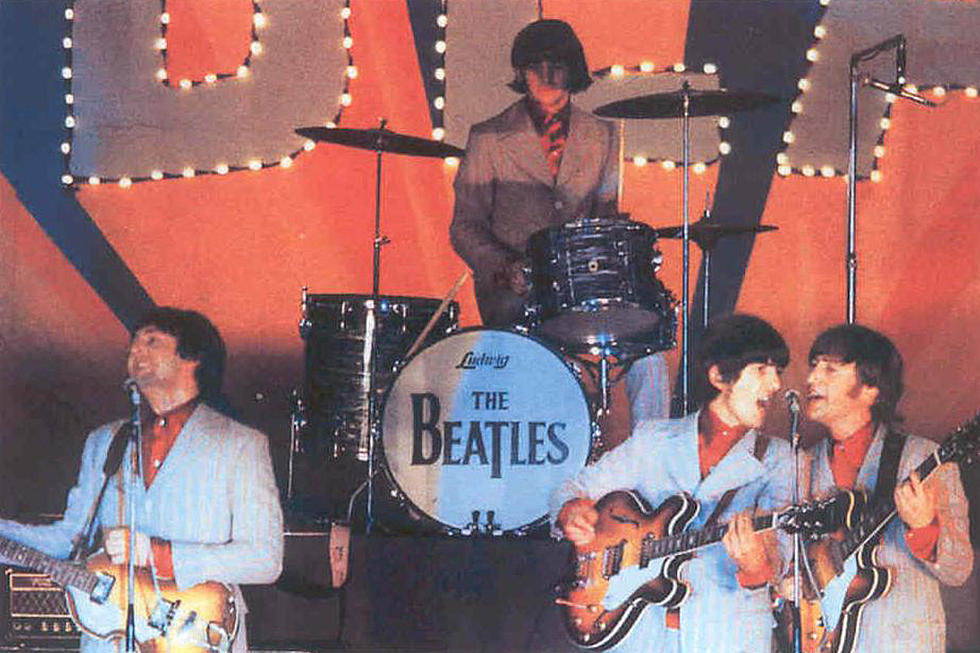

When we meet Taeko as a young girl in 1966, it is in the midst of Japan’s economic bubble. 1966 marked the year the Beatles went on their tour to Japan, Germany and the Philippines. Clothing styles were shifting in Japan. Short skirts were all the rage. Taeko’s second-oldest sister even has a crush on an actress at the Takarazuka Revue, an all female group of Kabuki performers.

But like every other aspect of Taeko’s life, Japan also changes with time. Two decades later in 1982 when Taeko is now an adult, we encounter a more introspective character, and country. Fearing that Japan was losing its unique essence, many city dwellers became enamored by the symbolic image of Japanese village life.

The safflowers that Taeko picks are symbolic of this widening gap between rural and urban life. Historically, safflowers were a sign of luxury for those that could afford them in the city. The workers that lived in rural provinces like Yamagata, however, picked safflowers as a means of survival. There were no opportunities to romanticize or aestheticize these precious plants, even if they did produce a beautiful dye.

Like other “city folk”, Taeko also slips into this blissful ignorance.

Overlooking rolling hills and sprawling fields in Yamagata, she concludes, “This is the countryside. The real countryside.”

But her farmer friend, Toshio, pushes against this notion that nature is entirely separate from human life, that one can so easily distinguish between the urban Japan of the present and its rural past.

He replies, “City folk see forests, and woods and streams and they are happy because they think what they are seeing is nature. Apart from back deep in the mountains, almost everything you see here is the work of a farmer…. It’s sort of a joint venture between people and the earth. That’s how the countryside works.”

It seems that this tension between the past, the present and the future is not so easily resolved in just a week’s time. By interspersing Taeko’s past memories with her present-day actions, Takahata blurs the conventional linear nature of time.

Instead, time, like the countryside, becomes a negotiation between a person’s memories and the natural progression of life. This reflexive portrayal of time pushes its audience to think:

How much of yesterday will I allow to seep into today? How much of today will I allow to seep into yesterday? What about tomorrow? And if there is no sharp boundary between any of these concepts, how do I grow?

For a movie titled Only Yesterday, looking towards tomorrow is at the core of the story. Takahata isn’t ignorant to the difficulties of transitioning into adulthood. Instead of shying away from this awkwardness, Takahata leans into the discomfort. There isn’t one distinctive way to read or digest Taeko’s memories. They both debilitate and inspire her. They make her soar and they also paralyze her.

I think many can relate.

As much as a person or even a nation may like to package the past into one specific identity, its porous nature will always find a way into the present. Just like a curious twelve year older, yesterday will climb on board and evaluate who today has become and why. It will force today to think about old crushes, family arguments and forgotten dreams. And after enough time, today will climb on board and wonder who tomorrow will become and why.

And the cycle begins again.

But this constant back-and-forth does not necessarily demoralize Taeko nor does the movie make it seem like this cyclical nature is inherently bad. On the contrary, there is hope to be found with every cycle that occurs. Tomorrow will one day become yesterday but each day doesn’t have to feel as it did at twelve years old, it can take on its own identity.

Taeko’s favorite song may be the best way to understand this maze of oscillating memories:

“If today is not good,

If tomorrow is not good,

There will be tomorrow.

There will be the next day

If the next day is not good,

There will be the day after that.

There will be tomorrow,

No matter how much time passes.”

If one day you find yourself accompanied by your yesterday self, maybe the best thing you can do is just look outside the window and enjoy the sunset. There will be another one tomorrow but it won’t be the same as today.

Leave a comment